Studio Ghibli and Disney are two of the most influential animation studios in history, but their worldviews are as disparate as night and day. Disney has built a global empire by taking its beloved characters and turning them into billion-dollar franchises, whereas Studio Ghibli has deliberately shied away from over-commercialism.

This stark contrast is no accident as Ghibli’s reluctance to mass merchandise is a deliberate choice to preserve the artistic integrity of its films even at the cost of lost profit. In a recent interview, Toshio Suzuki, co-founder and former producer at Ghibli, disclosed some of the lesser-known studio regulations that will blow your mind.

Studio Ghibli’s reluctance towards merchandising

In an interview with Yahoo! News, Studio Ghibli’s co-founder and former producer Toshio Suzuki opened up about the studio’s approach to limit Ghibli’s beloved characters from being over-commercialized. Suzuki explains that this philosophy stems from the belief that excessive commercialization dilutes the emotional and artistic value of the characters and they would ‘die instantly’. He explains:

One time, everyone got on our case about it, saying, ‘You’ve got to sell more.’ Someone from one particular company even said, ‘We could raise the sales to 200 billion yen just by ourselves.’ It’s not a joke. If they did that, then Ghibli’s characters would die instantly. I want Ghibli’s characters to have a long life.

Whereas most animation houses would jump at merchandising the moment they got the chance, Ghibli did things differently. When My Neighbor Totoro came out in 1988, there was no official merch of any kind.

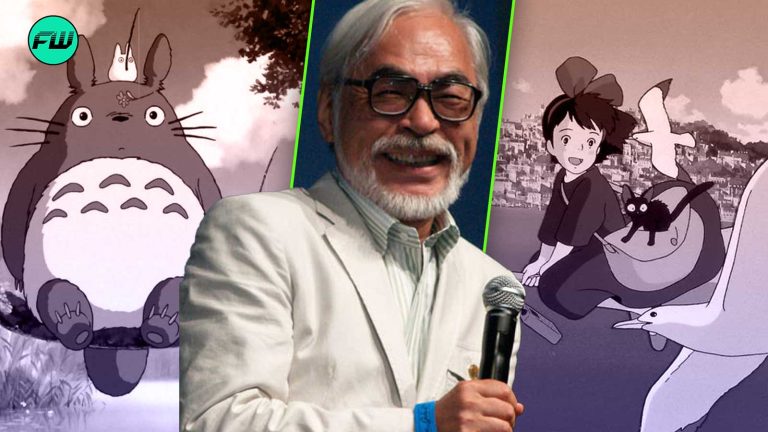

Two years later, the first Totoro dolls came out, and even that was only because the doll maker, Sun Arrow, made the samples so good that even Hayao Miyazaki, who did not particularly like the idea of merchandising, had to give in a bit and approve them.

Suzuki also added that the studio imposed a limit on its merchandising revenue at 10 billion yen. If they go beyond that limit, the person responsible will be criticized publicly in front of all collaborating companies.

Honestly, this kind of self-control is rather rare in the entertainment industry, where most studios just go for unlimited expansion. Ghibli’s beliefs are quite contrary to how another major animation studio, Disney, operates, where they just keep reimagining, merchandising, and re-packaging their characters everywhere.

Why Ghibli’s approach is Disney’s worst nightmare

From Mickey Mouse to Frozen, Disney ensures their characters remain in our heads, and our wallets. For Ghibli, the concern is that this would devalue the emotional investment that the audience has in their movies. Totoro, Chihiro, and Kiki live in their own worlds, uncorrupted by corporate greed.

Disney princesses are reimagined and repurposed for generations to come, but Ghibli characters are locked in time, just as they were intended to be. Disney lives on nostalgia but also relies on reinvention. Old films are remade (The Lion King, Aladdin), extended into new franchises (Toy Story 4), and incorporated into billion-dollar universes (Marvel, Star Wars).

Ghibli will not, however, look back at past work in the same manner. Miyazaki has even spoken out against sequels, saying that his tales are intended to be standalone. By maintaining its characters as sacred as possible, Ghibli gives them an aura of something greater, something human.

Their availability as few, precious commodities, and the fact that there are no sequels, further perpetuates this mystery. It’s a tactic that Disney cannot adopt without breaking the foundation of its business model. However, in spite of its commitment to avoiding mass merchandising, in recent times Ghibli has faced increasing pressure to adapt.

With Miyazaki’s return for The Boy and the Heron and the studio’s partnership with streaming platforms like Netflix, there’s speculation about whether this philosophy can survive in the modern entertainment landscape. However, as of now, in a world dominated by franchises, Studio Ghibli truly stands as a rare example of storytelling that prioritizes longevity over profit.

Most of the Studio Ghibli films are currently available to watch on Netflix.

This post belongs to FandomWire and first appeared on FandomWire